Remembering the AIDS Epidemic: Callen-Lorde Looks Back to Look Forward

December 1 marks World AIDS Day, an international day to reflect on the epidemic, remember lives lost and celebrate advancements that now save lives.

New York City was one of the epicenters of HIV and AIDS when the epidemic began in the 1980s. As such, health care providers across the city were hit hard as they struggled to comfort patients amidst terrifying prognoses, stigma and painful deaths. Providers that were part of the communities the virus disproportionately impacted—including gay men and people of color—were hit even harder. This includes people who were working at Callen-Lorde, which was founded in 1969 and was an essential part of the city’s response to the epidemic.

We’ve chosen to commemorate this World AIDS Day by showcasing the lifesaving work our current Associate Director of Medicine for HIV Services Dr. Rona Vail completed from the beginning of the epidemic onward. Rona describes what it was like working on the frontlines of a mysterious and deadly virus, the lessons she’s learned and what still needs to be done to end stigma and end the epidemic.

We hope you’ll take time to learn from Rona, who represents what Callen-Lorde is all about: Using lived experience to connect with patients, affirm them and move forward together.

What was it like working on the frontlines at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic?

I was a second-year medical student when the first cases of unusual pneumonias started. There was a whole thing of, what could this be? Shortly after that came an article about strange cancers in gay men. So it was clear something was going on. Throughout the rest of my training and residency it was AIDS-related conditions filling the wards of the hospital. Really strange things. It wasn’t until 1985-86 that we knew what the virus was—we just knew there was a virus causing strange infections and previously healthy people were dying from rare diseases like PCP pneumonia, retinitis…Personally, it was my friends, my community. As a medical provider it was so hard to see.

I didn’t immediately go into HIV care [after residency]. I had wanted to do international health and I did that for a few years, and when I came back to New York my former mentor from my residency program asked me to run an HIV clinic on the Lower East Side at [NYC Health + Hospitals] Gouverneur. I had been out of the country for three years and he said, “I think you’ll catch up pretty quickly. What they need is someone who has compassion to run this clinic.” So I was the medical director of the clinic.

I don’t like war analogies, but it definitely felt like we were in a war. The staff was very tight and very connected to each other because we were dealing with these horrors and tragedies every single day. In 1991 up through 1996, we would have team meetings every two weeks and start the meetings by saying the names of the people who had died since our last meeting and reflecting on them and talking about them. In a rare week it was nobody, but in most meetings it was anywhere from 1-5 people.

It was very moving work for me, but it was also very draining. In 1994 I told my medical director that I didn’t think I could do this anymore because I was just so emotionally drained from it. He told me to take a month off, just get away and travel, take time and go. And so my partner at the time and I traveled. We went to New Zealand and Fiji, as far away as we could from New York City, and we traveled and hiked and scuba dove and did all these things and came back and I was ready to go again. So I stayed in it. If I hadn’t had that, I think I would’ve burnt out like so many people burnt out. A lot of medical providers from those days started [using substances], had mental health issues, died by suicide…It was a really painful time to be a medical provider. Very fulfilling and wonderful with a lot of emotional moments, but it was also really painful. Being part of the community—a lot of providers were working with their communities—it is such a painful loss to see members of your community dying like this.

Rona at a Pride march, 1980s or 1990s

How has the landscape of treatment changed?

In 1996 it started to shift. We started to get our first highly active medications. For the first time there was this big sense of hope that we’d actually keep people alive and they’d be okay. That tempered in the late 90s when we realized our meds had many side effects and were fragile—their effectiveness would wane after a year or two, because what we now understand is the virus was mutating against those drugs pretty easily and figuring out a way around them. The euphoria didn’t last that long. But then in the 2000s we got better meds and got to the place we are today. Today, for anybody newly infected, almost all of them can take a single tablet per day and live their lives. We now have long-acting injectable treatments too which completely change HIV.

For some people, taking meds every day is very challenging. A lot of people—even though HIV has been transformed into a very treatable illness—many people still live with the stigma of being HIV+. Certain communities are much harder hit and there’s much less acceptance—Black folks and Latino and Hispanic folks are very disproportionately impacted still, and a lot of that I think is around homophobia and AIDS phobia. There are still a lot of people getting their diagnoses late because they don’t test because they don’t want to know. There are still people who have a really hard time coming to terms with being HIV+. Now, the fight is to get people to feel comfortable with who they are and that they can live a normal life. It’s not a thing of shame to be HIV+.

I don’t go home at night and cry anymore. It’s nothing like it used to be. I enjoy my job in a way that was hard in the 1990s. I feel like I can make a difference, prevent HIV, treat HIV. The difference we made in the past was keeping people supported as they were dying at 25, 35, 45. It was so painful. Painful deaths, people in wheelchairs going blind, families who were terrified to touch them. Really brutal years. For a lot of us, there’s a PTSD aspect too, thinking about those years. But they’re also important.

A year ago I stopped doing HIV primary care because I’m getting close to retirement. Many of us who started out doing HIV medicine and treatment are aging out and retiring. And so a lot of knowledge of those early days is starting to fade. I’ve decided in these last years that my focus is on training, because I want to train the younger generation to be good and confident HIV providers. I want to instill in them that sense of history—where we’ve been, where we are now. Most of what I’m doing is prevention, PrEP and sexual health, and teaching and training.

Callen-Lorde community members marching in a 1980s Pride parade, when we were known as the NYC Community Health Project

How are you imparting your knowledge?

I do 1-1 mentoring and talk about peoples’ cases, but also do larger case conferences with groups of people. It comes up organically when someone presents a patient who’s been positive since the 1990s. Depending on what that patient’s issues are I’ll talk about what might’ve been going on in the 90s and what they’ve been through. I think people are aware that it was terrible but not the reality of what that was like. Our providers are very much engaged at that level. A lot of them care about the history of our community.

What is the biggest lesson you teach providers who haven’t had this life experience?

That the reason patients may not come in for their appointments or take their meds is not a character flaw. It’s usually about their relationship to their HIV status and the relationship of people around them to the virus. Do they have support? Are they out to their family? Are they out to their partner? Are they out in the world? There are people who have isolated completely after their status—never had sex again because they could not imagine sharing that with anybody else. I know that’s an extreme case of internalized stigma, but I think it’s about sensitizing providers to what might be going on with patients. Also, when people are caught in a cycle of addiction or dealing with mental health challenges, HIV might be the last thing on their brain. It’s about knowing where people are at. There’s definitely a higher rate of mental health issues within the HIV+ population (but plenty of well-adjusted people too).

So it sounds like the combination of education, ending stigma and LAIs are the keys to moving forward.

Ending stigma is the biggest thing. The biggest reason people don’t take their meds is stigma, depression, substance use.

Are you concerned about the euphoria for LAIs and new medications going away quickly?

The vast majority of patients are on pills. We’ve learned a lot more about HIV than we knew in the 90s, so I don’t think we’ll get to that place [where euphoria fades]. What used to be hard is people would run out of options. They’d go through all the medicines, all the mutations and resistance to the medications, and we’d be waiting for the next medications while their T cells were dropping and their immune systems were getting weaker. We have an arsenal of new medications now, so we don’t have anybody at Callen-Lorde that we can’t treat for their HIV. That was not true in the past.

It’s possible in five years these drugs will be gone too, but there’s a really good pipeline of newer drugs. We don’t see the resistance we used to see; it’s much harder to develop. These new meds are easier to take and they last longer in the body.

In those earlier regiments people were amazing. They took pills all day. [For one regimen] someone had to find five times per day where their stomach was empty to take a pill, which you just can’t do. People would take 18 pills a day and they did it, but it was really hard. Now people are taking a single tablet once per day that is very hard for the virus to mutate against and we don’t see the same side effects. It’s so different. I don’t worry about us running out of meds. For someone who is newly infected today, I don’t think they’ll have trouble at all.

Would you say the number of new infections coming in is too high or has it leveled off?

Every new infection is one infection too many because we have the tools now to prevent HIV. My bullhorn is around prevention and PrEP—making sure people are aware of it and can get access. They can here whether they’re insured or not.

[New infections] are primarily in younger people, the 18-26 age group, and people of color. Black men… Black women are infected at much higher rates than white women and I think it has to do with stigma and fear and lack of information.

Do you think a vaccine is possible?

There’s a lot of work being done, but the more we learn, the more difficult we realize it is. The virus is so simple it’s able to change itself so quickly. It’s hard. But they’re developing broadly neutralizing antibodies to fight the virus, and now we realize if we combine three of them it stops the virus. I don’t think we’re on the verge of a cure, but I remember when I started HIV care I didn’t think I’d make it my career. But 40 years later…I think we’re closer than ever in learning about ways to treat the virus. But we’re not there yet.

I don’t think it’s a lack of funding that’s preventing us from finding answers. There’s a lot of science happening around the world.

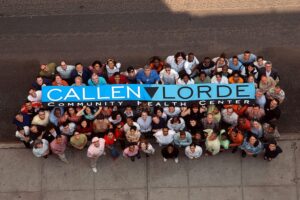

Callen-Lorde staff, early 2000s

What are some ways to help end stigma, given that it might mean that patients aren’t coming to Callen-Lorde?

I think we have to go into communities—recruit the pastors, the places people go to get support and spiritual relief. We have to talk to community providers about this. In our own practice, we have to make sure people know this is a virus. It’s not a judgement.

What tools can you give patients to help people manage everything outside their diagnosis?

Connecting people to support groups can be very powerful. Individual therapy, external organizations like GMHC that do social things…helping people to know other people can be a good way to help patients get away from the shame and stigma that they’re feeling. The exciting thing is, for so many patients HIV really is the least important of their issues. They come in because they need their meds and labs but they really are living lives where HIV is in the background. I think that’s where we want to be with everybody. We get there more and more.