This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

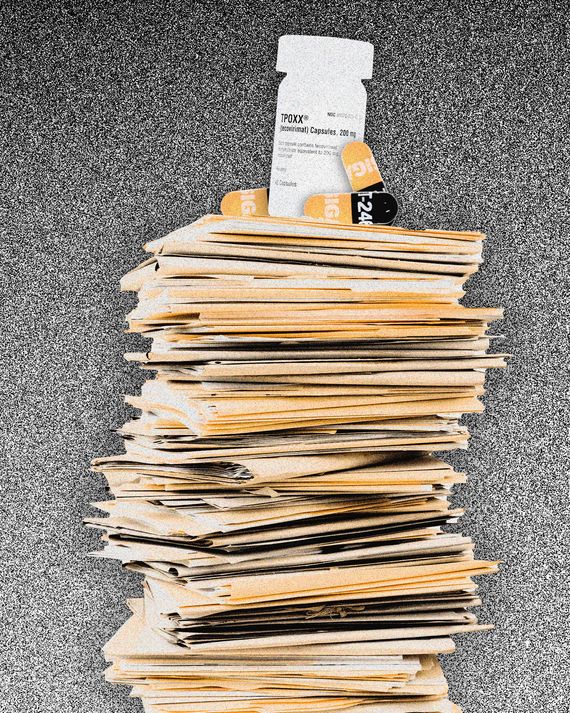

Normally, the small team of researchers at Manhattan’s Callen-Lorde Community Health Center spends its days doing the nitty-gritty work of compiling data and patient interviews that undergirds studies on trans health, HIV suppression, sex work, or any number of issues affecting the LGBTQ+ community. But over the past week or so, the clinic’s researchers have been sidetracked by thousands of pages of paperwork that have nothing to do with the clinic’s studies — forms that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention require health-care providers to fill out each time they prescribe TPOXX, an antiviral drug that has shown promise in fighting monkeypox.

“This burden of paperwork is not sustainable,” said Dr. Asa Radix, an infectious-diseases expert who heads Callen-Lorde’s research division. “We’re lucky to have four researchers working on this full time all day long, but I don’t know how a regular practice could ever manage. We had 24 referrals on Monday and more people calling looking for TPOXX.”

In the meantime, those who contract the disease face agonizing pain. While monkeypox can be fatal in Central and West Africa, patients in the U.S. have primarily turned to hospitals for pain treatment, according to the CDC. Lesions on the genital and anal regions can be excruciating (one person said he cried every time he urinated) and can spread to other sensitive areas like the eyes. The CDC recommends people with monkeypox isolate until lesions clear up and the skin is reformed, a process that can take up to four weeks.

New York City now has more than 700 confirmed cases of monkeypox, an orthopox virus similar to smallpox, and Dr. Radix is one of a chorus of health-care providers saying the barrier to access TPOXX is far too high. While most drugs require a prescription and a trip to the pharmacy, TPOXX is not commercially available, which means all prescribers must go through the federal government to acquire it from the Strategic National Stockpile. Because the Food and Drug Administration approved TPOXX for use against smallpox, the antiviral can be prescribed for off-label use only if the prescriber and patient adhere to a strict, cumbersome protocol. In order to get the drug, health-care providers must contact state or local health departments or the CDC. To do so, prescribers need to submit detailed information on each patient to the FDA and the CDC. The folio must include photographs of the patient’s lesions, the prescriber’s resume, and a daily journal kept by the patient once they’ve received the medicine. Additionally, all patients must undergo formal consent procedures. The paperwork is entirely in English and, Dr. Radix said, it forces trans and nonbinary patients to choose between checking the “male” or “female” box. All told, providers estimated that each TPOXX prescription required two to four hours of paperwork.

“I just can’t imagine every provider would have the willingness or the capacity to be able to do this,” said Lindsey Dawson, director of LGBTQ+ health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation. “There are levers that the CDC or FDA could use to streamline the process, and it’s our understanding that the federal government is working on doing that.”

Red tape is the latest hurdle for health officials responding to the monkeypox outbreak, which has climbed to more than 14,000 confirmed cases around the world. The first cases outside of Central and West Africa, where the disease is endemic, were detected just two months ago. Since then, in the U.S., people most at-risk of contracting the virus — men who have sex with men — have been assured that, because monkeypox is closely related to smallpox, the country’s health-care infrastructure is well-equipped to handle the outbreak. In reality, the federal government has been slow to react.

“If there was any biological threat that the U.S. should have been perfectly suited to respond to, it’s monkeypox,” said Dr. Jay Varma, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine who served as Bill de Blasio’s senior adviser for public health during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Despite having a pretty good understanding of the disease, a test for it, a vaccine to prevent it, and a drug to treat it, the U.S. has stumbled to deliver all of that to people where they are getting sick. Why did the U.S.-government response get delayed like this when we, more than any country on earth, should have been ahead of it?”

TPOXX, also known as tecovirimat, was fully approved by the FDA for use against smallpox in 2018. Because smallpox has been eradicated, the FDA approved TPOXX under the “animal rule,” meaning the agency deemed data from animal tests sufficiently proved the drug was effective and tests on healthy human subjects proved it was safe.

“The federal government’s logic in this situation is that smallpox represents an existential threat to the U.S.: It’s an agent of bioterrorism that is very rapidly spread,” said Dr. Varma. “Their logic is that this was only approved for that and, in contrast, monkeypox is not a lethal infection during these current outbreaks in the U.S. or North America. Therefore, you could make an argument that monkeypox is not eligible for this animal-rule exception, because it is possible to enroll people with monkeypox in randomized studies. The counterargument to that is that the approval for tecovirimat was based on a monkey model — nonhuman primates having monkeypox. We actually have data from the animal whose biology is closest to humans for monkeypox as opposed to an animal model of smallpox.”

Experts say federal officials can do one of two things to make prescribing TPOXX easier. The Department of Health and Human Services can declare a public emergency, suspending the CDC’s protocol requirements, according to Sean Cahill, director of health-policy research at the Fenway Institute. Alternatively, the FDA or CDC can develop an emergency-use protocol, streamlining the process — a move endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“We have these tools at our fingertips that, if we mobilize very rapidly, we have a chance of actually stopping this outbreak from extending further and becoming entrenched, endemic potentially, in our population,” said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, professor of epidemiology and medicine at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “The issue is that we have to push for all of these interventions — the testing, prevention, treatment — all together, rapidly.”

New York State Senator Brad Hoylman recently sent a letter to federal health officials urging swift action. “Because it’s impacting such a limited population — I hate to say, meaning gay and bisexual men — the sense of urgency is lacking,” he told Intelligencer. “I think Governor Hochul should declare a public-health emergency if that’s what it takes to get the federal government’s attention. New York City is the epicenter. There’s been foot-dragging at the federal level, and there was a shambolic response early on from city health officials. I don’t think we’re taking it seriously enough.”

More on monkeypox

- The U.S. Monkeypox-Vaccine Shortage May Last for Months

- Blowing Bubbles and Eavesdropping in the Monkeypox-Vaccine Line

- The Delay Behind the Monkeypox Vaccine Shortage